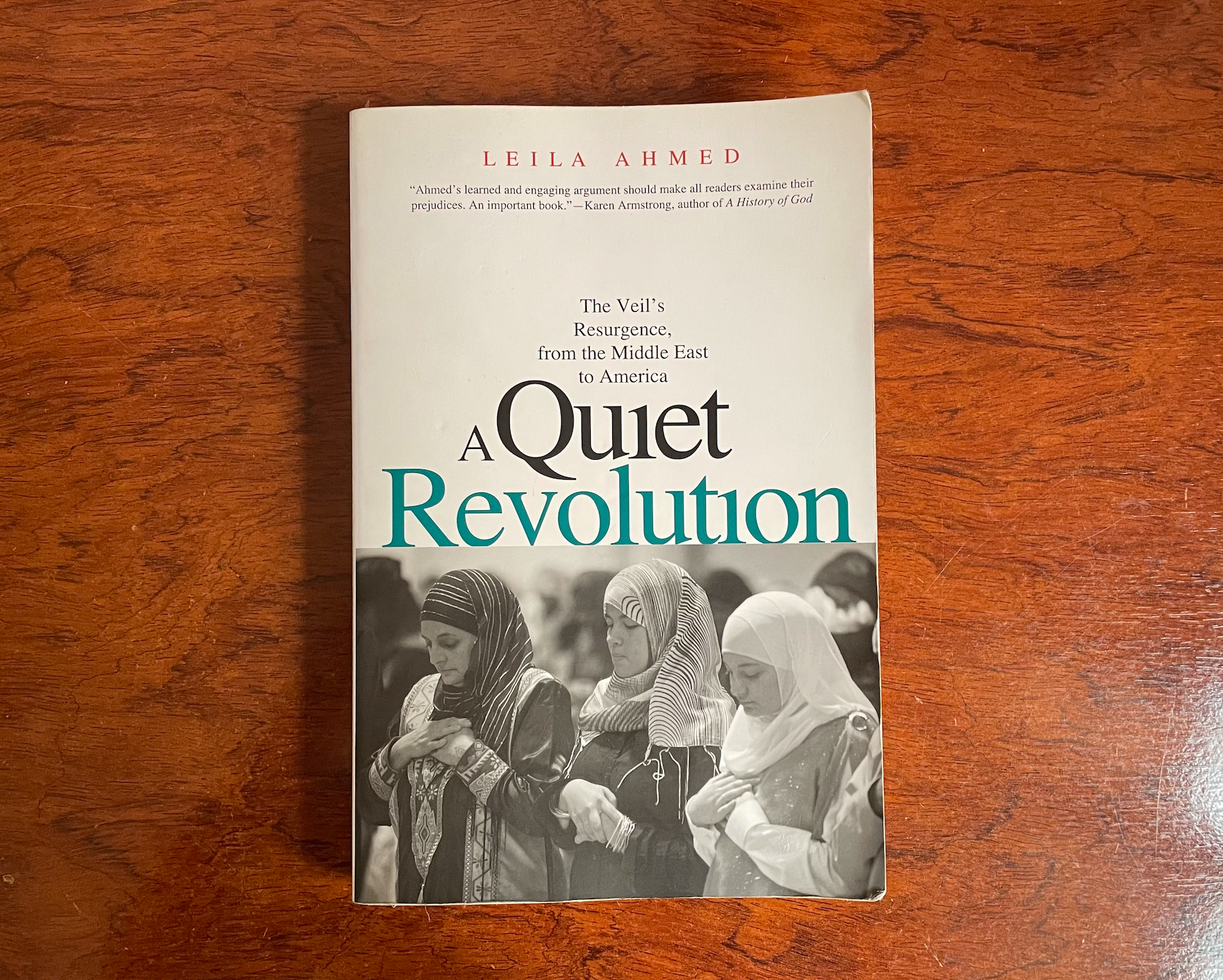

In this post, I’ll be reviewing A Quiet Revolution: The Veil’s Resurgence, from the Middle East to America by Leila Ahmed.

I picked this book up at the American University in Cairo, Egypt. I wanted something that was related to the context in which I was in. As well, I saw that the author was Leila Ahmed. Just a few months ago, I read another one of her books, A Border Passage: From Cairo to America—A Woman’s Journey.

I thoroughly enjoyed Ahmed’s personal writing and analysis of Islam in A Border Passage and knew I would likely not be disappointed by A Quiet Revolution.

What A Quiet Revolution is About

A Quiet Revolution would likely be considered by many to be an academic book. Ahmed shares her personal opinions and experiences quite sparingly throughout the text. She is mostly concerned with sharing the scholarship on the subject at hand, in addition to the observations she’s made that are relevant to the book.

The text is all about the veil in Islam, commonly referred to as the hijab. Ahmed traces how it came to be so prevalent in the Arab world and the West. She illuminates how much of the veil’s presence can be attributed to the rise of Islamism—a particular type of Islam that is concerned with the external components of religion such as going to mosque, activism, and community engagement.

Before Islamism, Ahmed shares, the religion of Islam was mostly one of the individual, meaning people prayed and had their own relationships with God but did not display aspects of their religion to the outside world. To be clear, it’s not like people were hiding their religion; it’s simply that Islam was more about one’s own internal faith.

Though the roots of Islamism can be traced back to the 1930s in the Middle East, it really took hold in the 1960s and 1970s. This new type of Islamism would incorporate aspects of Islamism that many Islamophobes associate with Islam in general today. For instance, militant Islam was beginning to take shape, as well as deeply conservative features of Islamism, one of which was the veil.

As much as Islamism had a part in women veiling, Ahmed also shows readers that the choice to veil for women was also personal. Speaking about women in Egypt during this time, Ahmed says that many women chose to veil because it gave them a sense of security and respect, while others veiled because they felt closer to God.

Nevertheless, Islamism did, as Ahmed notes, begin to influence women’s decision to wear veils. Women who did not veil in 1970s and 1980s Egypt, for instance, now found themselves to be a minority, who might be harangued by men or ostracised and even made to be non-religious. This was part of an overall shift to Islamism dominance.

American Islam in the Post 9/11 Era

In the second part of the book, Ahmed focuses mostly on American in the post 9/11 era. She traces how the ideals of Islamism began to reach the West and the United States in particular. What was really interesting, however, is that the ideas of Islamism began to be intertwined with ideals deeply rooted in the American tradition, such as justice for all and other egalitarian principles.

Ahmed dives extensively into the environment after 9/11. She illustrates how critiques against conservative Islamist ideas were able to be put forward, ones that before 9/11 would never take hold. She attributes this to the vulnerable position of Islam after the tragic event at the World Trade Center in New York City. People throughout Islam who would be fierce advocates of gender segregation and the superiority of men over women would be unable to assert their positions in this environment, given the way Islam was positioned in Western society.

This space gave room for a uniquely American type of Islam that critiques aspects of the religion that would be ignored or silenced before 9/11. What’s interesting about this American Islam tradition is that many of the people leading it were also deeply rooted in Islamist ideals that were formed in the 60s and 70s throughout the Middle East. Here we have, then, a group of people who, at the same time that they critique inequity and who write critically about women in Islam, are deeply religious—many of these women, specifically, who wear hijab. What’s more, because of their involvement with Muslim American organisations, their voices became the dominant voices of Islam in America.

I love this about A Quiet Revolution. Ahmed exposes so many interesting paradoxes that she herself was surprised by. In so doing, many of the assumptions readers might have—particularly those from the West—are challenged. I had quite a few moments throughout the book where, even as a progressive, I realized biases I had about Islam and Muslim people. For these reasons, along with Ahmed’s skilled writing and rigorous research, I highly recommend A Quiet Revolution.

Rating: 8/10

‘Till Next Time, Travel Friends!